The Name

Who, What, Why?

Society of Irregulars… It is my understanding that the name of this organization invites misinterpretation.

Who are the irregulars, why are they irregular, and what are they selling? A Google search for Society of Irregulars directs instead to a popular book from 2020: The Very Secret Society of Irregular Witches. It is described as “one of the coziest reads of the year.” We operate in a slightly different wheelhouse, although I am sure the novel itself is very intriguing. This comparison to the Witches offers a good opportunity for clarification as to what we are and what we are not.We are first a business, an art gallery, and we sell our paintings. The featured artists are not considered rebels and the society element does not describe an exclusive group. It represents a concept to which the organization adheres. That is the concept of Irregularity.

The name is not original at all. It is taken from the French Impressionist painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir. In his son Jean’s memoir he recalls his father floating out many profound thoughts in life. A frequented idea was that of Irregularity. There are many quotes that brush on this and one in particular stands out to me:

“I propose to found a society. It is to be called ‘The Society of Irregulars.’ The members would have to know that a circle should never be round.”

As far as I know this society was never created and Renoir appears to not have appreciated mathematics at all. Of course the sciences were not his vocation so we can grant him artistic leeway. But why have I turned this idea of imperfect circles into the name of our enterprise of painters? It is because irregularity is a quintessential notion of art, and the evidences of this are endless.

It would be fruitless to try and offer a definitive explanation. Instead I am providing a parable from Renoir’s childhood in nineteenth century Paris, and his career as a porcelain painter. This little anecdote might suggest a bit of what we are about.

———

“And there’s a certain something about hand-decorated objects. Even the stupidest worker puts a little of himself into what he is doing. A clumsy brushstroke can reveal his inner artistic dreams. I prefer a dull-witted artisan any day to a machine…”

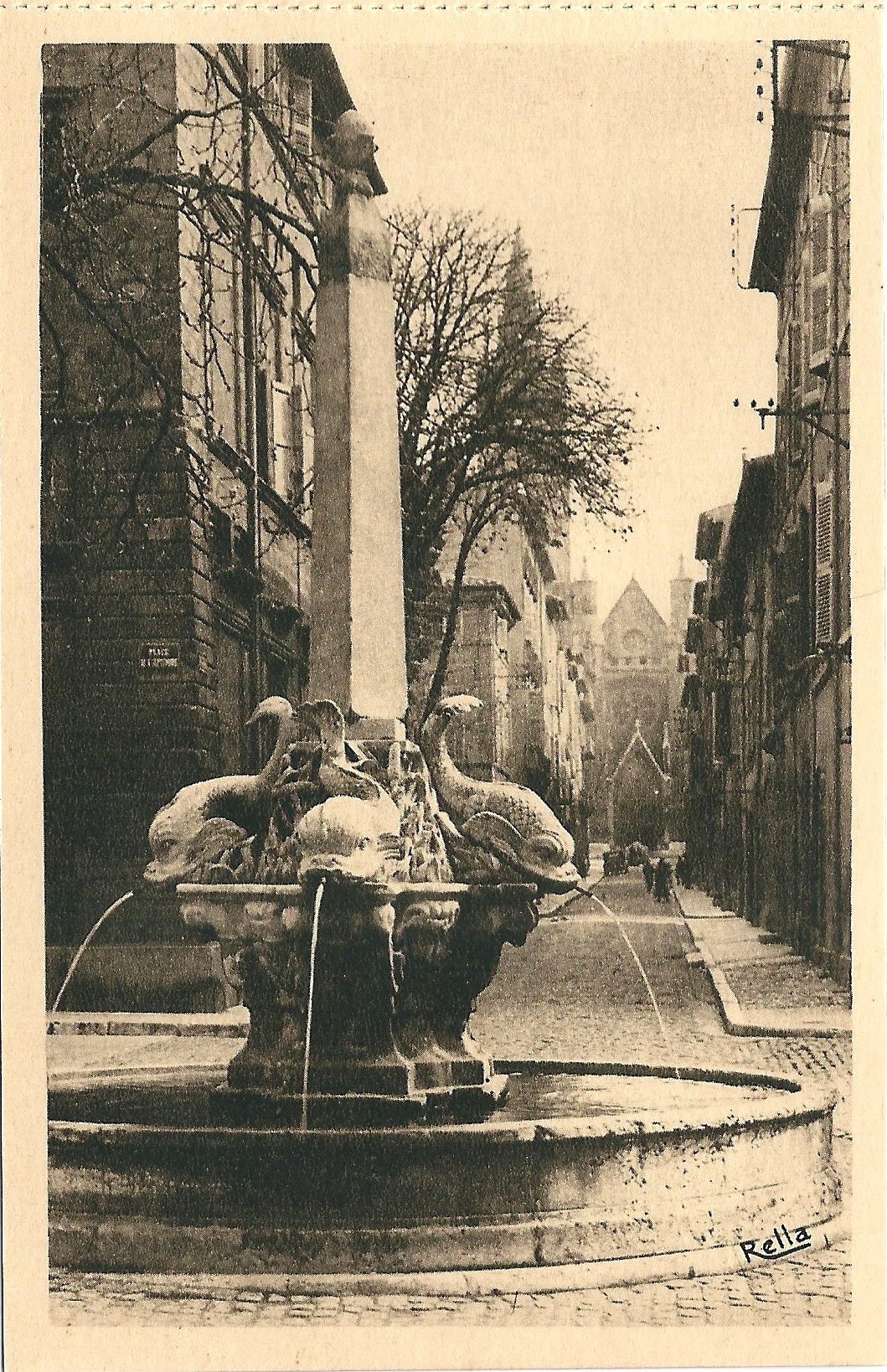

Young Renoir grew up in a quaint neighborhood in the shadow of the Louvre with half-timber houses and winding narrow streets. His father was a tailor and his shop was the ground floor of the family’s apartment as was customary of tradesmen. Dad grew tired of his son drawing on the floor of his workroom with tailors chalk, but he could not deny that the sketches were impressive.

At thirteen Renoir began an apprenticeship as a decorator of porcelain and china. He had a proclivity to it and quickly went from painting the borders of plates to doing the historical figures in the middle. The profile of Marie Antoinette was of highest demand.

“We owe that to the guillotine—the Bourgeoisie love martyrs, especially when they have had some wine.”

He was a quick master. His fellow workmates referred to him as “Monsieur Rubens.” But in 1858 industrial progress brought the death kneel. The process of stamping designs on the center of plates had become perfected. China would now flow from factories with tall smokestacks instead of small first floor family workshops. The owner of Renoir’s porcelain works decided to sell his shop and retire to the country.

But seventeen year old Renoir was not ready to surrender the craft. He formed a cooperative with his fellow workers and commenced “a battle of speed” against the career killing factory. They worked feverishly painting robust Venuses and brawny Apollos. By imagination and elbow grease they surpassed the production of the industrial machines.

Renoir proudly approached the dealers with hand decorated originals, but they were not interested. Their appeal to the mass-produced dishes was that each one was identical and perfect.

“I was beaten from the start by this insane passion for monotony so strong in our day that I had to give up.”

———

A twentieth century architect named Christopher Alexander said, “there is a central quality which is the root criterion of life and spirit in a man, a town, a building, or a wilderness. This quality is objective and precise, but it cannot be named.” The quality “is never twice the same, because it always takes its shape from the particular place in which it occurs.” It is something situational; something irreplicable.

An irregularity is incongruous to whatever is assumed correct, and what is genuine in this world fits no mold. In the reality of nature no two faces, no two leaves, and no two moments are exactly the same. It is the endless variety that creates an organic harmony. In the words of Paul Cézanne, “art is the harmony that runs parallel to nature.”

Nature is the ultimate teacher. It is our ancient ground and our continuous spring of inspiration. It reveals itself where a character radiates. The decorated plates of Renoir and his friends had a bit of themselves in them. This bit of themselves is a manifestation of nature within. A clumsy brushstroke can speak more truth than a methodical one. If life could be described as a succession of mistakes and learnings leading towards a complete experience however lengthy or brief, the process of painting can be seen in such a way too. This is the way something is made whole, and can only exist exactly as it is in its present circumstance. That is nature in art.

It is the occurrences of nature in art that Society of Irregulars is invested in. We are here to foster the eye in finding these wondrous occurrences within the renderings of our own artists’ paintings as well as looking to artwork from the past. It is our hope that together in discussion we will see more as we invest our energy in critical observation. We will pursue this through writings, interviews, open forums and art exhibitions both in person and virtually. In this collective endeavor we will dig deep in search for meaning in the mystery of our world by looking longer and sharing what we see.